Data-based services are increasingly present. As a consequence, the algorithms and data they process play an increasingly important role in decision-making, with significant effects for human welfare and human rights. Thanks to algorithms, you can obtain good booking recommendations or an efficient travel route for your trip. Of course, on the other side, you may also be admitted (or not) to the university of your choice, you may be granted (or not) a mortgage with a bank and you may be hired (or not) for that job you wanted.

It is often thought that machines are neutral arbiters: cold objects, calculators that can distinguish patterns which our human minds cannot (or refuse to) distinguish and make an optimal decision. But, is it really like that? Or are algorithmic decisions a way of amplifying, extending and making the kind of prejudice and discrimination that already prevails in society inscrutable?

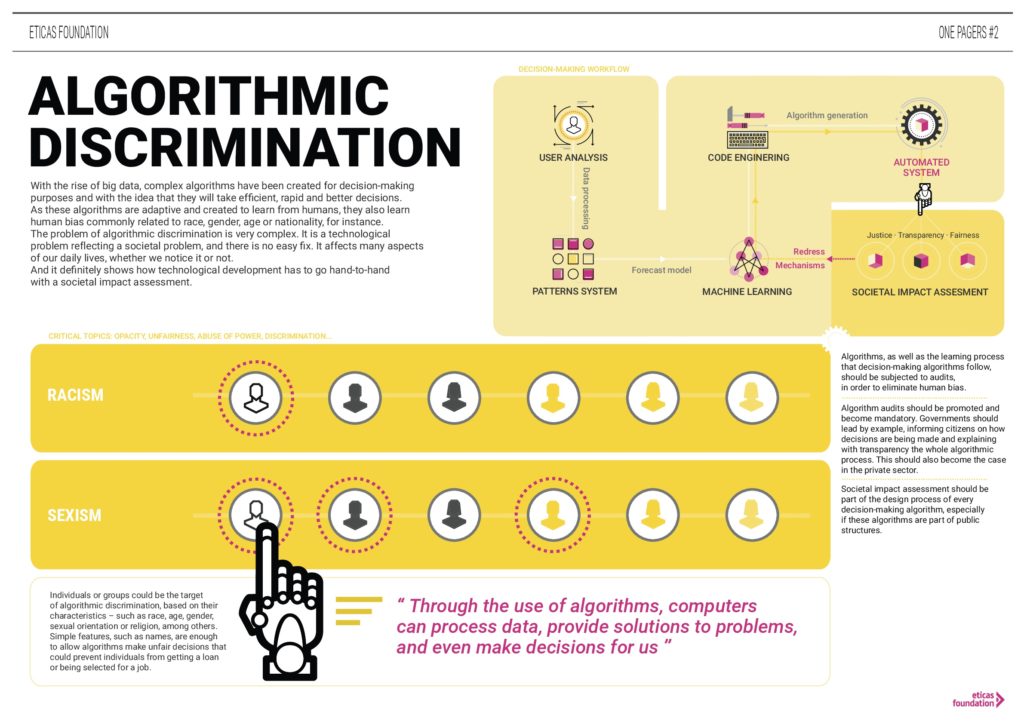

Advances in machine learning have led companies to rely on Big Data and algorithms, based on the presumption that those decisions are more efficient and impartial than the ones taken by humans. However, as the use of algorithms becomes more extended, numerous claims have also been raised demanding greater responsibility in their use, their design and their implementation, mainly because of their capacity to normalize and amplify social inequalities through algorithmic discrimination.

In spite of this, algorithms are becoming a key factor in numerous daily activities, at a speed that seems to exceed our capacity to understand their impact on our lives. That is why there is an urgent need to understand the role played by algorithms in society, to place the issue on the public agenda and to analyze the policies that can be adopted to guarantee the rights and equity of people in the context of algorithmic proliferation.

It is necessary to analyze the kind of problems raised by the increasing use of algorithms in society and also the regulatory proposals to adopt, such as the recent initiative of the City of New York to create a specific cabinet just for evaluating the equity in algorithms, or the proposals of the French Data Protection Authority and Working Group 29 of the European Commission on how to address these issues from the perspective of privacy protection.

With the advancing technological changes that characterize the information society, there comes a growing concern over all issues related to privacy, discrimination and automation. As Dournish (2016) argues, aside from discussions regarding the role that algorithms could play in everything from hiring practicies (Hansel 2007) to credit ratings (Singer 2014) or even the optimal temperatures in office buildings (Belluck 2015), “an awareness has developed that algorithms, somehow mysterious and inevitable, are contributing to the shape of our lives in big and small ways”.

Searching for “algorithms + discrimination” on Google today gives back more than 120 million results, which suggests a fertile ground for the trivialization of the challenges posed by the interaction between technology and society. That is why a rigorous taxonomy of the kind of impacts and externalities – positive and negative – of the algorithms is compelling. This would allow us for an understanding of the risks involved in the proliferation of the use of algorithms in a very wide variety of tasks and processes with important consequences for society. Only with this kind of knowledge can we advance designing efficient measures to be taken by the relevant actors involved, in order to mitigate any negative consequences.

Algorithms are social constructions converted into mathematical calculations. Like any other technology, they capture and reproduce social dynamics. Often, these social dynamics become entangled in obscure technical debates that undermine their understanding by the general public. Perhaps for this reason, in the media and in the popular imagination, algorithms are interpreted almost exclusively in terms of the so-called ‘algorithmic discrimination’, when an individual or a group of individuals perceive unfair treatment as a consequence of an algorithmic decision making, based on automated profiles. However, the profiles can also be used to apply positive discrimination or discrimination based on principles of fairness and justice. Therefore, reducing algorithmic impact to social exclusion hides the multiple dynamics that algorithms entail and over-simplifies the various processes of discrimination in a counterproductive way.

In algorithmic processes, profiling and discrimination not only arise from our individual qualities, but also relating to the characteristics of those around us. This is what Dannah Boyd (2014) calls “discrimination by network”. In this sense, understanding algorithms strictly from the analysis of individual characteristics does not lead to a rigorous categorization of their risks and possibilities, nor to a systematic diagnostic of their future perspectives. On the other hand, in recent years, numerous authors have argued that we must replace the concept of discrimination with that of justice. Justice is, together with efficiency, one of the two major categories of concerns identified by Zarsky (2016), also emphasizing two characteristics of the algorithms that generate special concern: on one hand its opacity and, on the other hand, its automated nature. However, contrary to what this author proposes, Friedler et al (2016) insist on the “the impossibility of fairness” in algorithmic processes.

The lack of consensus on the social impact of algorithms suggests the need to develop a conceptual framework capable of integrating a high degree of complexity, based on an analysis of the relationships between the actors and processes and devices that come into conflict when a negative social impact is perceived. This task requires the application of a multidisciplinary approach to the systematic observation of algorithmic processes, considering them as technological processes integrated in particular contexts and specific practices.

A framework of algorithmic regulation must rise from a deep knowledge of the field, the actors, the practices and the impacts, in order for it to respond adequately and efficiently to the challenges posed by the use of algorithms in different contexts, in addition to the importance of the values and expectations of the actors involved and affected by these challenges. At the end of the day, laws and regulations are social consensus coded in legal terms. For this reason, they often appear long after a new social phenomenon has had a clear and measurable impact on society. However, given the extraordinary speed and high social impact of new technologies, society cannot afford to let the breach between the time it takes for a new technology to have a significant social impact and the time when we are finally able to protect those who may suffer from the negative externalities of this technology, to grow further.

In this sense, we propose a ‘reverse engineering‘ of existing regulatory frameworks to identify how and why they have arisen, what they can tell us about the societies that proposed them in the first place and what kind of impact they have had. On the other hand, it is necessary to analyze proposals for translating human ideals (ethics, equity and justice) into forms that can be understood by algorithms along with concepts like accountability. These issues can be addressed through a mapping of social conflicts arising from the use of algorithms, which in turn will serve to identify the problematic points in the design of existing policies and to suggest a toolbox of good practices.

If algorithms are becoming the key to numerous daily activities, the need to understand their impacts on society is an urgent matter. It is not an easy task. Framing this issue, understanding what algorithms actually are and what role they can play, requires a systematic analysis of algorithmic processes and the generation of new conceptual, legal and regulatory frameworks to guarantee human welfare and human rights in a globalized and interconnected society. The difficulty of the task is indeed proportional to its need; it is nothing less than one of the main challenges for social progress in the 21st century.